Alice Henwood Earl (1871 - 1961)

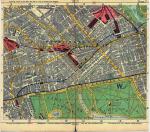

Another intriguing possibility is whether Alice retained contact with her natural mother after adoption. The 1881 census reveals Frances Caroline, then aged 35, unmarried and employed as a cook by the Goldsmith family living at 45 Bryanston Square, St. Marylebone, which is only a few minutes walking distance from Crawford Street where Alice was born. A glance at a contemporary map also shows how close Bryanston Square is to Connaught Square Mews and to Titchborne Row where John Lawn, and possibly Alice, went to school.

Was there regular, or any, contact between Frances and daughter Alice? It would be heart-warming to know that there was; more realistically, however, Frances said goodbye to Alice when she handed her over to the Lawns, believing, rightly of course, that Alice had a better chance in life as part of an established family. Crucially important, moreover, was that Alice, in such a setting, would be far less likely to continue the pattern of youthful pregnancy and unmarried motherhood that was her fate and that of her mother Caroline. Since Frances was in service at 8 Porchester Terrace in 1891, she would have been in comfortable walking distance from 8 Devonport Mews. In 1901, aged 54, unmarried and still employed as a cook at Porchester Terrace, Paddington, Frances was only a few streets away from Cambridge Place where recently married Alice lived with husband Ernest and young son George.

| 1901 census on 7 Cambridge Place, Paddington | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ernest | ALDIS | M | 33 | Coachman domestic | b.Bexley |

| Alice | “ | Wife | 29 | b.Marylebone | |

| George | “ | Son | 10mths | b.Paddington | |

Again, it is tantalisingly tempting to imagine that Frances would have had the pleasure of seeing her grandson George; possible, but unlikely. Doubtless, Alice’s adoptive parents, still resident in Devonport Mews in 1901, would have enjoyed that pleasure and the profound satisfaction gained from knowing that the baby they had adopted and raised had grown into a model wife and mother.

| 1901 census on 8 Devonport Mews, Paddington | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| James W. | LAWN | M | 75 | Cab proprietor (working on own account) | b.Limpenhoe |

| Elizabeth | LAWN | Wife | 60(sic) | b.Nottingham | |

By this time, incidentally, John Lawn, now 33 and employed as a clerk, was living with his in-laws, Henry and Amy Perry, in Fulham Place, St Mary, Paddington. Married to their step-daughter Agnes, John has a son and daughter of his own:

| 1901 census on 13 Fulham Place, St Mary, Paddington | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry | PERRY | M | 52 | Tailor (working on own account at home) | b.Exeter | |

| Amy | PERRY | Wife | 58 | b.Plymouth | ||

| John W O | LAWN | son-in-law | M | 33 | Clerk (worker) b.London | |

| Agnes | LAWN | step-dau. | M | 31 | b.Plymouth | |

| Agnes | LAWN | grand-dau. | 5 | b.London | ||

| John W C | LAWN | grandson | 4 | b.London | ||

Cambridge Place and Fulham Place being only a few streets apart, it seems likely that the two families would have met, and that Alice and Agnes as young mothers would have exchanged information and experiences.

At least as the wife of a coachman to Lord Swaythling Alice had the benefit of living in some of the more elegant and less polluted parts of London. The quality of the air in London at that time in the winter was all but insufferable. Coal fires and the industries in London, tanning, especially, filled the air with smoke and fumes. Fog, so graphically described by Dickens in his novels, was an ever present menace in the winter, causing darkness in the middle of the day. The combination of cold and bad air quality meant bronchitis and other lung complaints were rife.

Housing conditions in the working areas in the early 20th century were dire: cramped, dark and with poor sanitary and washing facilities - and caring for babies a full time job. Towelling nappies, disposable ones were more than 60 years away, had to be boiled daily. There were no manufactured baby foods which are now standard fare - mothers had to prepare, boil and mash suitable food for their children. There was no central heating - rooms were cold, windows iced over in the winter and children had to be well wrapped up against the cold at night. Even as servants in the grand houses in the nicer parts of London these winter conditions would have applied to Alice and Ernest as they cared for their young family.

Before very long, however, Alice would have needed all the help and comfort she could get from Agnes and from her own family. Following the birth of her son George in 1900, Alice had a daughter, Elizabeth Alice, born 16 December 1901 at 9 Kensington Court Mews, Kensington Town. That she named her daughter Elizabeth testifies, surely, to the respect and affection she had for her adoptive mother who, in turn, would have been delighted with and inordinately fond of her granddaughter. But tragedy was soon to disrupt this seemingly model contented family. Baby Elizabeth developed tubercular meningitis and died, aged 20 months, at Saltwood near Hythe; the death was reported by Ernest Walter, “present at the death Saltwood”. Was the family on holiday at the time, visiting friends or relatives? Or did Ernest’s work as chauffeur to the Samuel family take him this far from London? We cannot know.

What is certain, however, is that Alice was distraught at her loss which, understandably, cast a shadow over her entire existence but which she never allowed to come between her and her main business in life, being a good wife and mother. Infant mortality, always tragic, was still relatively common at the start of the 20th century. Alice would have known other families similarly affected, and her own adoptive parents had experienced the same loss. Doubtless she would have been comforted and reassured by Elizabeth Lawn; and in any case she now had two sons to raise since Richard Walter was born in 1905.

Other deaths followed, happily in the natural order of things. James William Lawn, the only father Alice had ever known, died 13 February 1910, aged 79 (the death certificate has 89!). By this time he and Elizabeth were living at 8 Warwich Crescent, Paddington, apparently with their son John and daughter-in-law Agnes who reported the death. James is still described as a “cab proprietor”. Six years later, 24 December 1916, Elizabeth died, also aged 79, still living with her son and daughter-in-law at 8 Warwick Crescent, though she ended her days in Paddington Infirmary. Her son John reported the death. To complete the pattern of deaths, Alice’s birth mother, Frances Caroline Earl, died 11 October 1927, aged 82 years, of chronic bronchitis. The death certificate describes Frances as “of 1 Merton Road, spinster, of no occupation, other particulars unknown”. The death was reported by E. Philbrick, occupier of 28 Marloes Road, Kensington South, London (presumably Kensington Institute) where Frances actually died. That she lived to such an advanced age is remarkable, given the straitened circumstances of her life. Since, however, her grandmother Caroline also exceeded 70 years, and her daughter Alice achieved a magnificent 89 years, there is perhaps evidence of a strong genetic predisposition to longevity.

Little is known of Alice’s life with Ernest during the first half of the 20th century. They had no more children after Richard Walter, survived two world wars, and saw their two sons reach adulthood, marry, and have their own children. Fortunately, a useful indirect source of information exists in the account of the Samuel Montagu family written by Ivor Montagu who was born in 1904, the fourth child and youngest son of Louis Samuel, 2nd Baron Swaythling, and his wife Gladys (Goldsmid). Ivor Goldsmid Samuel was born at 28 Kensington Court, and in December 1901 Alice and Ernest were living at 9 Kensington Court Mews where their daughter Elizabeth Alice was born. Exactly when Ernest became coachman, subsequently chauffeur, to Lord Swaythling is not known; but it seems likely, on the evidence of the propinquity of the two residences, that he already held the position by 1901. Ivor Montagu records that Townhill, the family’s country house estate in Southampton, was rebuilt around 1912 prior to the family moving there. “The coachman learned to drive,” he writes, noting that the family’s first car was a Lorraine-Dietrich. Was Ernest Aldis the coachman/chauffeur in question? Probably, since the writer reports an incident from his youth which involved Richard Aldis, the second son of Alice and Ernest, born in 1905 and therefore almost an exact contemporary of Ivor Montagu. He recounts how he led a group of younger children to the orchard, presumably at Townhill, on a ‘scrumping’ expedition. They were caught by the head gardener and “my especial friend, Dick Aldis, the coachman’s younger son, was beaten by his father”. The ringleader, merely admonished by his father, experienced guilt and embarrassment in consequence. Kensington Court and Townhill were still the family homes in 1927, but the latter was sold around 1930 by Ivor Montagu’s older brother, Stuart Albert, who became 3rd Baron Swaythling on the death of his father in 1927.

Certainly Alice and Ernest ended their days in a retirement cottage, Blackthorn Lodge, on the Swaythling estate in Southampton. Ernest, who would have retired about 1934, died first, 6 January 1955, aged 86; and Alice, who had remained at Black House Lodge after Ernest’s death, 19 February 1961. By the time this account came to be written by one of their grandchildren, both of their sons, George Mafeking and Richard Walter, were dead; and little of a personal nature seems to have survived to illustrate their long lives which were both ordinary and unusual.

One event which, quite properly, was recorded was their silver wedding anniversary in 1949 when the couple were, respectively, 80 and 78. The present writer remembers that occasion, and fortunately a photograph of it has survived.

Fortunately, too, the present writer remembers Alice’s wonderful personality, even in old age; she seemed always to be laughing, to see the funny side of things, and to delight in putting visitors at ease and plying them with food. She was a remarkable woman, loved by everybody, whom it was a great pleasure and privilege to know; the only regret is that time and opportunity so limited those occasions.